The New York SHIELD Act

- History of the SHIELD Act

- What does the SHIELD Act protect?

- What types of information does the SHIELD Act safeguard?

- Who needs to comply with the SHIELD Act?

- Who enforces the SHIELD Act and what are the penalties?

- How do you become compliant with New York’s SHIELD Act?

- SHIELD Act Compliance Checklist

- SHIELD Act vs. CCPA vs. GDPR: What are Some Differences?

- The SHIELD Act in Relation to the Broader Idea of Data Protection

- The Future of the SHIELD Act

New York’s Stop Hacks and Improve Electronic Data Security Act (“SHIELD Act”), codified under New York’s General Business Law as Article 39-F sections 899-AA and 899-BB, came into effect in two parts. On October 23, 2019 the law came into effect with respect to the changed breach notification requirements. On March 21, 2020 the remainder of the act came into effect, including the enhanced security measure requirements for businesses that handle the personal information of New York residents.

The SHIELD Act amended existing New York breach notification statutes by broadening their applicable scope, increasing the size of penalties, and requiring businesses to adopt reasonable but stronger security protections for personal information. It imposes heavier security requirements on any business that collects or maintains private information on New York residents.

Violations of the SHIELD Act are enforced exclusively by the New York Attorney General. For violations of the breach notification mandate, the New York Attorney General may bring actions for civil penalties of:

- up to actual damages and consequential financial losses (if notice of a data breach is not provided) incurred by residents for violations that are negligent, or

- the greater of $5,000 per violation or $20 per failed notification for violations that are knowing or reckless (with a $250,000 limit)

Violations of the security measure requirements can incur a penalty of $5,000 per violation.

Compliance with the SHIELD Act requires the creation and maintenance of a security program that includes administrative, physical, and technical safeguards for data privacy management.

History of the SHIELD Act

The New York SHIELD Act was signed into law on July 25, 2019. However, amended breach notification obligations began on October 23, 2019, and reasonable security measure obligations began on March 21, 2020.

How did the regulation come to exist?

In 2017, New York’s Department of Financial Services published its cybersecurity regulation, 23 NYCRR Part 500, which imposed security standard requirements on the financial service industry. Two years later, New York’s Attorney General urged the state legislature to continue this trend. This culminated in the SHIELD Act which deploys further protections for the ‘private information’ of New York residents.

The regulation (Senate Bill S5575B) sought to update New York’s data breach notification law and bring the state’s data security obligations into line with more modern technology. This was accomplished by broadening the scope of information covered, broadening the definition of a data breach, and by requiring reasonable data security programs be established.

What does the SHIELD Act protect?

The SHIELD Act protects the private information of residents of the state of New York. Unfortunately, the law does not explicitly define “resident.” However, the law does apply broadly to “any person or business that owns or licenses computerized data which includes private information of a resident of New York”. This requirement is clear, private information of any New York resident in an electronic format needs to be safeguarded. This should also include employees, provided they are New York residents. Essentially, New York is attempting to mitigate the possibility of and subsequent impact on its residents from data breaches.

What types of information does the SHIELD Act safeguard?

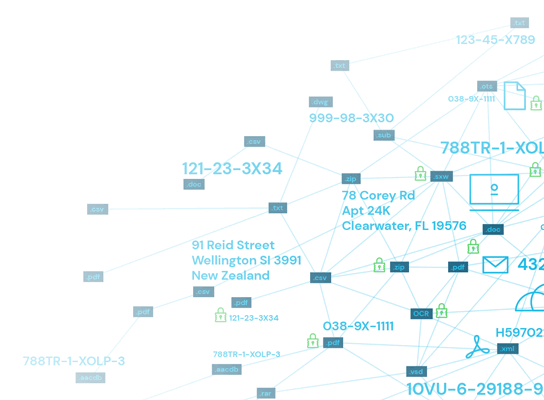

The SHIELD Act protects “private information”, which is a term of art. Private information requires a combination of personal information (name, number, or other identifier) and a listed data element identifier. These data element identifiers include:

- Social security number

- Driver’s license number or non-driver identification card number

- Financial account or credit and debit card numbers in conjunction with information that would permit access to the account

- Financial account or credit and debit card numbers if circumstances exist that the number could be used to access the financial account

- Biometric information

- A username or e-mail address in combination with a password or security question and answer that permits access

So, private information is personal information (like a name) in combination with another identifier (like a social security number or even login information for email or online accounts).

Who needs to comply with the SHIELD Act?

The SHIELD Act imposes its security and breach notification obligations on regulated entities which is defined as “any person or business that owns or licenses computerized data which includes private information of a resident of New York”. These regulated entities are required to “develop, implement and maintain reasonable safeguards to protect the security, confidentiality and integrity of the private information” in their possession or licensed to them as residents of New York state. This component also appears to be extraterritorial, meaning that New York is telling businesses across the globe that they need to implement reasonable security measures to protect the private information of New York residents.

Who enforces the SHIELD Act and what are the penalties?

New York’s Attorney General has the right to bring enforcement actions and to seek injunctions under the SHIELD Act. The privacy protections contained within the Act lack a private right of action.

The Attorney General can seek penalties of $5,000 per violation for knowing or reckless violations of the Act’s security requirements.

The SHIELD Act increased the caps on civil penalties that the Attorney General can seek. The penalty for failing to properly comply with the Act’s breach notification requirements has increased from $10 per failed notification to $20. This penalty now has a hard cap of $250,000. Enforcement actions for a failure to provide notice also are subject to a three year statute of limitations after the earlier notice being given to the Attorney General or affected residents. In addition, enforcement cannot be brought after six years from when the company discovers the breach unless a company took steps to hide that a breach occurred.

Worth noting is that if a court finds that notice was not provided the SHIELD Act authorizes the court to award damages for actual costs and even consequential financial losses.

In sum, violations of the SHIELD Act are enforced exclusively by the New York Attorney General and can include:

- Penalties for violating the breach notification requirements:

- a. Up to actual damages and consequential financial losses (if notice of a data breach is not provided) incurred by New York residents for violations that are negligent

- b. Up to $5,000 per violation for violations that are knowing or reckless. Subject to a $250,000 limit, or

- c. $20 per failed notification in the event of a data breach. Subject to the same $250,000 limit.

- Penalties for violating the security measure requirements can reach $5,000 per violation.

There is currently no private right of action.

How do you become compliant with New York’s SHIELD Act?

The SHIELD Act’s requirements can be divided into two distinct categories: (1) the reasonable security measures obligation and (2) the data breach notification obligation.

Reasonable security measures

The statute lists its expectations for a reasonable security program. (Those are discussed in the SHIELD Act Compliance Checklist below.) In short, the SHIELD Act requires the adoption of security measures that includes at a minimum, administrative, technical, and physical safeguards for the private information of New York state residents. Administrative safeguards seek to manage an organization’s operations by influencing things like employee training, company policies, and data loss prevention procedures designed to mitigate the risk and damage from the mishandling or breach of personal information. Technical safeguards are things like cybersecurity, access controls, and software designed to preserve the confidentiality of data. Physical safeguards are locks and other barriers that limit the physical access to systems that store private information and the facilities that house them.

The SHIELD Act also recognizes that a company’s compliance with other data security regulations satisfies the reasonable security measure requirement. These include compliance with:

- GLBA

- HIPAA

- HITECH

- New York’s Department of Financial Services 23 NYCRR Part 500, and

- “any other data security rules and regulations of … the federal or New York state government.”

The statute considers entities subject to these requirements to be a “compliant regulated entity.”

Did New York create exceptions to the security obligation requirements?

In short, no. This law is very broadly applicable and has only outlined two possible mitigating factors on a business’s responsibility to comply.

- Publicly available information is not private information.

- The SHIELD Act recognizes that creating security programs may be difficult for small businesses and alters its expectations with respect to small businesses (in light of a few factors).

Worth noting is that the public information exception is also narrow. It does not excuse a business from compliance beyond the limited scope of use for the public information. Essentially, if a business uses public information and private information, they will be expected to comply with the obligations of the SHIELD Act.

The small business ‘exception’ is better understood as a lowered expectation for their security practices, rather than safe harbor or immunity for small businesses. Small businesses must still attempt to comply with the security requirements of the SHIELD Act and are still required to implement reasonable security programs. Small businesses are defined as having fewer than fifty employees, less than $3M in gross annual revenue for each of the last three years, or less than $5M in total assets. The understanding of what is acceptable as compliant varies when considering three statutorily outlined factors:

- The size and complexity of the small business;

- The nature and scope of its activities; and

- The sensitivity of the personal information the business collects.

So, while all businesses with private information on New York residents must comply, what will ultimately be a reasonable security program varies based on whether the business is simple like a pizza shop or complex like a small financial institution or startup biotech company.

Data breach notification (and changes to the statute)

The data breach notification obligations stemming from the SHIELD Act came into effect in October of 2019. They utilize the same broad and encompassing definition of private information that applies to the security obligations.

An obligation to send out a breach notification arises if a “breach of the security of the system” is discovered or detected, or reasonably believed to have occurred, that allows access or acquisition to a system that has private information on “any resident of New York … without valid authorization.” The SHIELD Act expanded the original requirement to now also include unauthorized access instead of just acquisition. This change dramatically expands the scope of the data breach obligations and further necessitates the need for robust technical safeguards that can detect an intrusion that allows either access to or acquisition of private information.

To determine if a breach has occurred, the Act recommends that you look for indicators that information:

- is in the physical possession or control of an unauthorized person

- has been downloaded or copied, or

- has been used in an unauthorized way such as if fraudulent accounts are being opened or identity theft is reported.

These breach notification requirements make it essential that your business have the security infrastructure necessary to recognize and detect if information has been viewed or used by someone that was not authorized to do so.

Exceptions to the data breach notification requirements

“Good faith access to, or acquisition of, private information by an employee” for business purposes “is not a breach … provided that the private information is not used or subject to unauthorized disclosure.” The SHIELD Act does not consider inadvertent access or disclosure by an authorized individual to be a data breach necessitating notification. This exception applies only if a reasonable determination was made that the exposure is not likely to result in misuse, financial harm, or emotional harm. Essentially, this exception permits the use of private information for business purposes if there is not likely to be any misuse or harm stemming from the use.

Additionally, data breach notifications that are compliant with GLBA, HIPAA, HITECH, New York’s 23 NYCRR Part 500, and “any other” federal or New York state regulation or law will satisfy the SHIELD Act’s requirement.

Form and delivery of notices in the case of a breach

A proper data breach notification informs the affected New York residents in “the most expedient time possible and without unreasonable delay.” Affected residents, the New York Attorney General (if over 500 residents’ information breached), the New York state department, the New York state police, and the consumer reporting agencies (if over 5,000 residents’ information breached) all need to be provided notice of a breach. Notices to the government organizations need to contain the timing and content for notices to affected individuals, and the approximate number of affected persons from a breach. Notices to affected residents can be done through a variety of media, including:

- Written or Electronic (if the subject has consented to electronic notice)

- By phone or through email (if the breached information doesn’t include email addresses in combination with passwords)

- Conspicuous posting on the business’s website

- Notifying major statewide media

- Other substitute notice if the cost exceeds $250,000, the affected individuals exceeds 500,000, or the organization does not have the necessary information to provide notice

These notices must include:

- The contact information of the organization making the notice

- The contact information of state and federal agencies that can provide information on security breach responses for preventing identity theft

- A description of the categories of private information implicated in the breach, including the specific elements of private information that were believed to have been accessed or acquired

The act also contains additional reporting requirements. For instance, the New York Attorney General is to be notified within 10 days after a determination is made that the breach is unlikely to result in misuse or cause financial or emotional harm or within five business days of notifying the secretary of state when complying with HIPAA.

What was the timeline for businesses to become compliant?

The SHIELD Act is now fully in effect. On October 23, 2019 the law came into effect with respect to the changed breach notification requirements. On March 21, 2020 the enhanced security measure requirements for businesses that handle the private information of New York residents came into effect.

If your organization possesses the private information of New York residents, this law applies to you and your organization will need to begin compliance efforts immediately.

What is the audit process to identify shortcomings?

Shortcomings in compliance efforts can be addressed in a few ways. For instance, consider consulting our SHIELD Act compliance checklist against the policies and procedures within your organization. This will allow for a simple precursory way to audit your organization, but a more comprehensive approach by privacy and security professionals may be needed.

Another way to internally test compliance is to do a dry run of a breach incident with your organization’s employees to test policies, procedures, and training. This can directly test the deployment (or existence) of administrative safeguards like how employees follow procedures and their security training. Internal audits can also assess technical and physical safeguards. For instance, consider if all the devices within your company’s infrastructure are running the most current versions of your cybersecurity program and have maintained the same appropriate firewall configuration. Deviations or variance in the variations across devices may signal a need for further compliance efforts and pose potential risk vectors for a breach. This is just one simple step of many that your organization can undertake to test or audit its technical safeguards.

In addition, employees can also be used to assess physical safeguards like workplace security and the effectiveness of access controls. If your employees can get access to workstations or information security systems that they are not authorized on, then your organization will need to reassess its practices. A thorough and robust approach to assessing your security program is through a privacy risk assessment. This can be done internally but can be immensely time consuming, so if your organization does not have the capacity or manpower to spare, consider hiring a privacy consultant or using a privacy risk management software.

Your security program can also be audited externally by hiring a consultant. These consultants can conduct a privacy impact assessment and provide consultation on how to bring your organization into compliance. A privacy impact assessment will serve as a comprehensive way to audit your company’s compliance shortcomings.

SHIELD Act Compliance Checklist

If your business operates digitally and collects information, presume that the New York SHIELD Act will apply to you or your organization. Every company that has a New York customer or the private information of a New York resident will need to implement the basic requirements of this Act.

The SHIELD Act recognizes an effective data security program as one that incorporates administrative, technical, and physical safeguards. To comply, the SHIELD Act lays out its requirements rather clearly and simply by requiring the implementation and maintenance of a reasonable data security program. Below is a checklist of items for SHIELD Act compliance.

1. Security Program

If your organization does not have a comprehensive security program, consider developing an action or to-do list. Through that you can identify both your organization’s security weaknesses and needs but also demonstrate tangible progress to regulators.

2. Administrative Safeguards

Ask if your organization has administrative safeguards that satisfy the SHIELD Act? If no, implement the policies and procedures that the SHIELD Act suggests including by:

- Appointing someone to coordinate the security program

- Identifying reasonably foreseeable internal and external risks

- Assessing safeguards and compare them to identified risks

- Training employees in security procedures

- Selecting service providers that also maintain appropriate security practices and requiring them in contracts

- Assessing security programs as circumstances and threats evolve

3. Technical Safeguards

Does your organization have reasonable technical safeguards, such as sensitive data discovery or data classification, that satisfy the SHIELD Act? If no, implement the policies and procedures that the SHIELD Act suggests including a system that:

- Assesses risks in network and software design

- Assesses risks in information processing, transmission, and storage

- Detects, prevents and responds to attacks or systems failures

- Regularly tests and monitors the effectiveness of access keys, key controls, systems and procedures

4. Physical Safeguards

Does your organization have reasonable physical safeguards that satisfy the SHIELD Act? If no, implement the policies and procedures that the SHIELD Act suggests including a system that:

- Assesses the risks of information storage and disposal

- Detects, prevents, and responds to intrusions

- Protects against unauthorized access to or use of private information (throughout the data lifecycle from collection to transportation and destruction or disposal)

- Disposes of private information within a reasonable amount of time after it is no longer needed

5. Considerations for Small Businesses

Small businesses (fewer than 50 employees, less than $3 million per year gross annual revenue, or less than $5 million in year-end total assets) should attempt to comply with the security program requirements, discussed in Points 1-4. However, the SHIELD Act recognizes that privacy compliance can be a difficult and expensive task. As such, there is some leniency for small businesses.

- Small businesses must still implement reasonable security programs (but the perception of what is reasonable shifts)

- Small business security programs will be acceptable if they are appropriate for the:

- Size and complexity of the small business

- Nature and scope of its activities

- Sensitivity of the personal information the business collects

6. Unauthorized Access Detection

Ensure that you have a system in place to detect the unauthorized access or use of information that would give rise to the SHIELD Act’s breach notification requirements. Train your employees to ensure they will also recognize when a breach may have occurred.

It is worth noting that the SHIELD Act recognizes compliance with GLBA, HIPAA, and other New York security regulations as being reasonable security measures. The same logic is applied to breach notification requirements, wherein they will also be satisfied if you comply with the requirements of other federal or state laws and regulations.

7. Breach Notification Procedure

Establish a procedure for issuing notices to those affected by a data breach, in the event that you detect one.

SHIELD Act vs. CCPA vs. GDPR: What are Some Differences?

Data subject/consumer rights

The SHIELD Act doesn’t bestow actionable rights to New York residents over how their data is used by organizations like those that we see in more comprehensive laws like the CCPA or GDPR. Instead, it recognizes that security programs are essential in this digital age and that data breaches can harm people. Which is a fundamental realization by the legislature to begin offering data privacy protections.

This means that, to comply with the SHIELD Act, organizations must only develop and maintain a reasonable security program, rather than implement additional new procedures that enable data subjects to exercise their rights.

Scope of the different regulations

The SHIELD Act generally imposes its obligations on “any person or business” that possesses the private information of New York residents. This approach mirrors the GDPR’s, which similarly does not have any threshold requirements for compliance obligations on businesses, governments, and nonprofits. In contrast, the CCPA requires a threshold be met for for-profit entities before compliance obligations materialize. The SHIELD Act also recognizes that small businesses may struggle to adopt a robust security program and explicitly states that the reasonableness of a security program shifts in relation to a small business with respect to its level of sophistication and the purpose for the private information. The CCPA accomplishes something similar through its threshold requirements that may not require small businesses comply.

The SHIELD Act was drafted to protect New York residents, regardless of where the private information is possessed or used. The CCPA similarly does this for California consumers and the GDPR does this to protect EU data subjects. As a consequence, applicability of the GDPR is extraterritorial per Article 3, using either an “offering of goods and services into the EU” theory or a “monitoring the behavior of EU data subjects” theory. Such applicability is true for the CCPA and apparently so for the SHIELD Act.

Enforcement and penalties

The SHIELD Act allows for enforcement actions brought as civil suits by New York’s Attorney General. This is the same approach as the CCPA. In contrast, under the GDPR EU member states utilize supervisory authorities, government agencies designed to promote data protection and punish violations.

The three laws take different approaches to the potential size of permissible fines, making an apples-to-apples comparison difficult. The GDPR authorizes data protection authorities to seek damages of up to 4% of a company’s gross global annual revenue, depending on the violation. The CCPA allows for recoverable fines of $2,500 per violation for unintentional violations and up to $7,500 per violation for intentional violations. These fine schemes can both reach astronomical amounts with a large-scale breach or when involving a large corporation. The magnitude of these fines helps to encourage compliance efforts and promotes the development of responsible privacy and security practices.

In contrast, the fine scheme within the SHIELD Act is much smaller and generally has a cap of $250,000 (but may include actual damages and consequential financial losses). Violations of the SHIELD Act’s security obligation requirement can incur $5,000 per violation and failures to provide notice in the event of a data breach can incur penalties of $20 per failed notice. The size of these fines is drastically smaller than those found within the CCPA and GDPR. This appears to reflect the limited nature of the SHIELD Act, which has less extensive requirements and does not attempt to go as far as the CCPA or GDPR with respect to data privacy obligations.

The SHIELD Act in Relation to the Broader Idea of Data Protection

According to a press release issued with the signing of the SHIELD Act bill into law, “The SHIELD Act is the result of over two years of work between The Business Council [a business advocacy group] and the Attorney General’s Office.” The implication here is that the law represents a balance of considerations involving the protection of private information versus imposing new (and costly) mandates on businesses. While the Act is a step in the right direction for data protection, it is largely an information security regulation. It serves to impose basic security requirements with the objective of preventing or mitigating data breaches. This contrasts with some of the sweeping data protection laws that bestow actionable rights to individuals over their data and impose robust obligations on organizations.

The Future of the SHIELD Act

The SHIELD Act may serve as a stepping stone for New York to adopt stricter data privacy and security regulations, such as the New York Privacy Act (NYPA). The NYPA is remarkable, owing to its introduction of the principle of a fiduciary relationship between data controllers and data subjects, as well as its requirement for opt-in consent to the sale of personal data to third parties. The proposed law also creates a private right of action for data subjects to pursue compensation against businesses that violate the law. Its scope lies in stark contrast to that of the SHIELD Act, which has proven to be non-controversial. In fact, the mandates of the Act are largely typical for state data protection laws.

While the legislative sessions of 2020 produced little in the way of new data protection legislation, voter approval of the proposed California Privacy Rights Act of 2020 (CPRA) may serve as a powerful catalyst for another wave of U.S. state data protection laws. If so, changes to the SHIELD Act are all but inevitable.