On March 10, 2021, a rights-based data protection bill proposed by Florida’s House of Representatives passed out of the House’s Regulatory Reform Subcommittee on an 18-0 vote to approve. The bill, H.B. 969, proposes a rights-based data protection regime similar to the California Consumer Privacy Act of 2018 (CCPA) and the California Privacy Rights Act of 2020 (CPRA). The proposed regime offers certain rights and protections for Florida’s residents and responsibilities for businesses that collect or process their personal information. The bill’s text draws significantly from the CCPA/CPRA, and I’d like to share noteworthy similarities and well as some differences.

Similarities of Florida’s data protection bill to CCPA/CPRA:

- Applicability to certain businesses: B. 969 applies to businesses anywhere in the U.S. (and potentially, the world) that conduct business in Florida and either (1) have global annual gross revenues in excess of $25 million; (2) annually receive, buy, sell, or share the personal information of 50,000 or more consumers, households, or devices; or (3) derive 50 percent or more of their global annual revenues from selling or sharing personal information about consumers. In doing so, the bill tracks the original approach to jurisdictional reach taken by the CCPA; the CPRA would later revise this to raise the 50,000 unit threshold to 100,000 and to eliminate devices from the total.

- Access, correction, and deletion of personal information: B. 969 grants Florida consumers the right to access a copy of their personal information held by a business and the right to have that information deleted (with some exceptions) following the CCPA. It also grants consumers the right to make corrections to personal information held by a business, following the CPRA.

- Private right of action: B. 969 features a private right of action that uses the updated language of the CPRA (which includes an email address with password or security question as protected information) and offers remedies of $100-750 per consumer or actual damages, whichever is greater, as well as injunctive relief. As with the CCPA/CPRA, there is an opportunity for a business to “cure” a violation. However, under the bill, this cure is not limited to data breaches but rather to any alleged non-compliance with the law, in contrast with the CCPA/CPRA.

- Definition of personal information: The bill’s definition of personal information is almost a word-for-word adaptation of the definition that the CCPA uses in section 140(o). The CPRA’s addition of “sensitive” personal information (e.g., a consumer’s precise geolocation) was not included, however.

- Opt-out/opt-in consent model: The bill tracks very closely the CCPA model for enabling opt-out consent, whereby a consumer has the right to direct a business not to sell that consumer’s personal information, a right to opt-out of the sale of personal information when a business so engages, and a right to notice from a third party already in possession of a consumer’s personal information and the opportunity to opt-out of sales or sharing of that information. Furthermore, the bill tracks the CCPA’s requirement of parental/guardian approval of the sale or sharing of the personal information of a minor 12 years of age or younger.

Differences of Florida’s data protection bill to CCPA/CPRA:

- Enforcement agency: The CCPA/CPRA will be enforced by a dedicated body, the California Privacy Protection Agency, starting January 1, 2023 (In fact, the Agency will be enforcing all California privacy laws). B. 969 will be enforced by the Florida Attorney General’s office.

- Employee data: The bill exempts employee information from its scope. The CCPA was silent on the matter, but some interpretations led to the belief that such information was in scope. After the CCPA’s passage into law, subsequent legislation (and the CPRA) clarified that employee information would be subject to the law starting on January 1, 2023.

- Business-to-business communications: The provisions of the CCPA/CPRA do not, at the moment, apply to personal information contained in business-to-business communications made in the context of due diligence. That exemption will expire, however, on January 1, 2023. The bill is silent on the matter, and presumably, such information is in scope.

- Privacy policy: B. 969 states that “[a] business that collects personal information about consumers shall maintain an online privacy policy, make such policy available on its Internet website, and update the information at least once every 12 months.” In contrast, the CCPA/CPRA does not per se mandate the publication of a privacy policy but does assume in many instances that a business will have one.

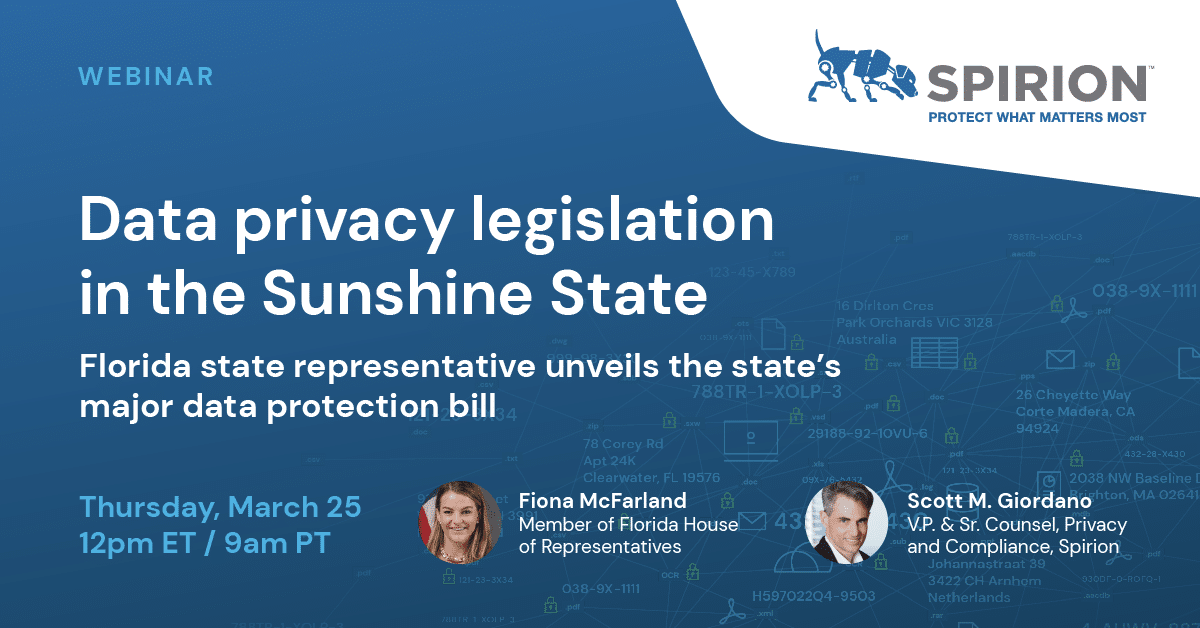

H.B. 969 has the support of Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis and is being steered through the legislative process by Rep. Fiona McFarland. The Subcommittee hearing video can be found here and watching it proved instructive for how the state’s legislative process functions. I spoke with Rep. McFarland on Spirion’s U.S. Data Privacy Trailblazer webcast, where we discussed considerations for the bill’s contents, balancing consumer rights vs. business burdens, and the prospects for the bill’s passage into law. You watch a webcast replay here. You can watch a webcast replay here..